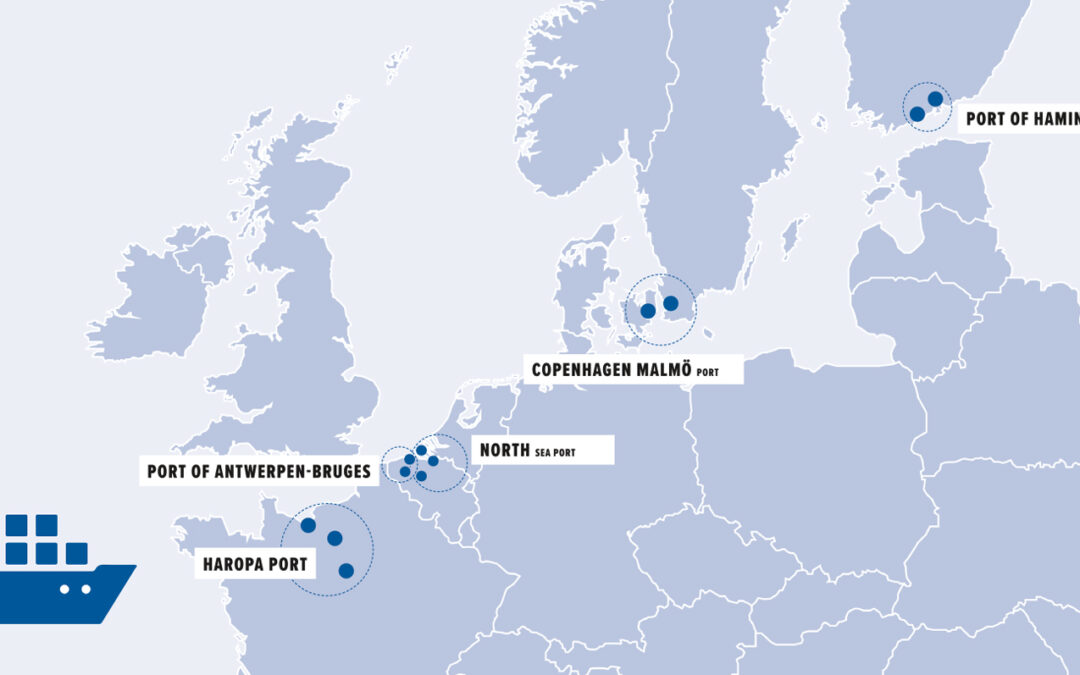

Many European seaports have merged over the past 20 years. What drove their decision to do so, and what obstacles were there along the way? LOGISTICS PILOT was on the case.

Credits: vectorstock-siraanamwong, flaticon, Copenhagen Malmö Port, Port of HaminaKotka Ltd., North Sea Port, Port of Antwerp-Bruges, Haropa Port

CMP: Bridge not a problem

The ports of Copenhagen (Denmark) and Malmö (Sweden) kicked things off in 2001. Copenhagen Malmö Port (CMP) was founded exactly one year after the opening of the Øresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden. “Everyone saw the bridge as a great opportunity,” reported Ulrika Prytz Rugfelt, Chief Communications and Sustainability Officer at CMP.

“There were hardly any doubts at all,” explained the CMP board member. “This was because many saw the merger as both a good example of cross-border cooperation and an opportunity for the ports to adapt to a new market.” The company was nevertheless granted a three-year trial period, but the business was already in full swing after only 18 months. “The biggest advantage is that the ports operate efficiently,” emphasised Ms Prytz Rugfelt.

Port of Hamina-Kotka: extreme resistance, then shared happiness

In contrast, achieving the 2011 merger of Finland’s Hamina and Kotka ports was a longer process. “Talks about cooperation between the two ports had been going on for 40 years, but one or the other was always against it – sometimes Kotka, sometimes Hamina again,” reported CEO Kimmo Naski.

How come? Both ports are only about 20 kilometres apart and had the same profile – containers, RoRo, general cargo and liquid and dry bulk. Moreover, they were both owned by local authorities and were also important for local politics – among other things because of their impact on employment. Investment was hotly competitive and, since it was feared that both locations would cease to develop, they merged.

The mood only changed during the financial crisis of 2008/2009, when both ports lost about a third of their respective total traffic. “The local elections were happening at the same time and many of the elected politicians were in favour of cooperation, including a port merger,” Naski recalled.

Customers welcomed the merger from the get-go, and capital expenditure has steadily decreased over the past years. There are also many operational synergies. “Traffic is handled where it’s best for the customers. All eight sections of the port now have their own profile,” reported the CEO.

Logistics Pilot

The current print edition - request it now free of charge.

North Sea Port: Dutch-Flemish port alliance aims high

Already connected by a canal, the Dutch Zeeland Seaports (Vlissingen and Terneuzen) and the Port of Ghent in Flanders, Belgium, only merged to form the North Sea Port in early 2018.

Last April, the 60-kilometre-long North Sea Port and the Port of Gothenburg signed an agreement on closer cooperation, focussing on building a network of medium-sized European ports and working on energy management within them. In working together, the ports also aim to strengthen their commercial interests and promote cargo flows between them.

Port of Antwerp-Bruges: aspiring to become a global port of the future

here had been repeated speculation about a possible cooperation between the Belgian ports of Antwerp and Bruges. After years of discussions and negotiations, the cities agreed to merge their two ports, under the name Port of Antwerp-Bruges, in February 2021. Their goal is to strengthen both ports’ position in the global supply chain and achieve sustainable growth.

Advantageous is that both complement each other considerably. Antwerp’s strength, for example, lies in transporting and storing containers, general cargo and chemical products, while Zeebrugge is a major port for RoRo traffic, container handling and the transshipment of liquefied natural gas.

This creates a number of synergies. “Containers that could not be handled in Antwerp were diverted to Zeebrugge, where capacity was available,” reported Lennart Verstappen, Corporate Communication Advisor at the Port of Antwerp-Bruges. In terms of liquid bulk, Zeebrugge handled a great deal of LNG, while the handling of chemicals in Antwerp was slightly down. “At total turnover level,” he continued, “the decline in containers is compensated by the good results in other sectors.”

Most read

Haropa Port: Seine axis logistics corridor for goods from across the world

A national port strategy was the deciding factor in France. In June 2021, the three French ports on the Seine axis, Le Havre, Rouen and Paris, merged into a single public institution, having already founded Haropa, an economic interest grouping, in 2012.

The aim was, among other things, to change the size dimension, become more resilient to economic changes and external influences, regain market share throughout the river corridor and unify governance. It also aimed to provide Paris with a maritime outlet and promote the energy transition through sustainable transport to the hinterland.

Even though the three ports had not been in competition with each other before and each had their specialities, strengths and weaknesses (containers for Le Havre, grain and agro-industry for Rouen, inland waterway transport of building materials and city deliveries for Paris), many fears that were more historical-cultural than economic nonetheless existed. None of the sites wanted to lose their respective specificities, their own identity and organisation. This situation was solved by introducing a new corporate governance that involved all stakeholders. (cb)